Banks “23/8 is 9/12-light – for now”

Recommendation

I’d advise caution on exposure to interest rate sensitive stocks for the time being.

Banks are particularly sensitive to fluctuations in long bond yields, the primary driver of the value of the big four banks.

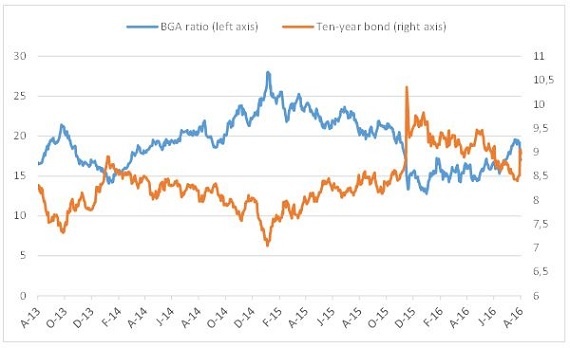

As the graph below illustrates, the share price of Barclays Group Africa has an inverse relationship to the ten year government bond yield.

Share price is the inverse of the bond yield

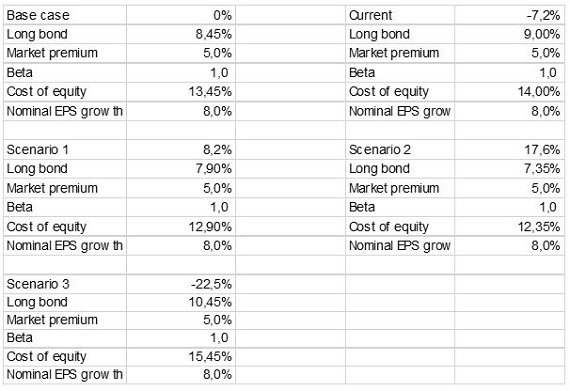

On the basis of my modelling, a 55 basis point increase in the ten-year government bond to 9%, which is what we have seen, reduces the present value of future earnings by 7,2% and thus the value of the share.

If the bond yield had to drop by 55 basis points then all else equal the value rises by 8,2% and if the yield fell by 110 basis points then the value rises by 17,6%.

However, if we have a repeat of Nenegate (let’s call it Pravingate) and we see yields spike by 200 basis points, which is what happened on Thursday, 10 December 2015, then the present value of earnings falls by 22,5% from the base case. In an environment of contagion, the negative impact is likely to be greater than in a static modelling scenario.

Bank share prices are already off 5% to 7% over the past few days and in the prevailing uncertainty prone to further weakness.

Valuing banks in the current context

The risk-dampening triumph that was the outcome of the municipal elections came to an abrupt upending on the evening of Tuesday, 23 August.

After a municipal election, that I described on 8 August as South Africa’s Brexit moment, there was a fortnight of respite from otherwise disturbing political trends. There was a re-emergence of confidence, manifest in bond markets and the currency.

The significance of the municipal elections process and outcome should not be underestimated but meanwhile underhand party-political forces overshadow this positivity to reignite investment hazards.

Political machination is the only possible cause behind an insidious ploy to besmirch a world-class finance minister through an accusation that is spurious in law and a travesty of due legal process.

Rotten politics makes for rotten governance if practiced through a kleptocractic cronyism indifferent to consequence. This nevertheless has immediate financial consequence through adverse market price signals, which in turn has real economic impacts.

South Africa is fortunate to have deep, liquid and sophisticated financial markets. Markets reward and markets punish. If a government cannot impose self-discipline and prudential management, markets bludgeon it in to doing so the hard way.

The twin forces of democratic accountability and free markets are an effective coercive counterweight to misrule.

Since last week, the 10 year R186 has risen by 55 basis points to 9%, the rand has lost 7% against the US dollar and the JSE banks index is 6% lower. Standard Bank, Barclays Group Africa and FirstRand are down 7% with Nedbank off 5%. Insurers such as Sanlam and Discovery are also softer.

Share prices of Barclays Group Africa, FirstRand, Nedbank and Standard based to 100

This is a small market movement relative to the rout following 9/12 or Nenegate. If there is a repeat of 9/12 in the near future all bets on the downside are off.

At this time, South Africa has to be showing real delivery on the fiscal and economic commitments made a few months ago.

The climb out of the abyss that was 9/12 was down to extraordinary cross-sectoral collaboration, in spite of attempts to sabotage the good work, but there won’t be a second chance to regain tentative assurance. Business, labour and public servants aren’t likely to get another invitation to join hands in London and New York to reassure interested parties abroad.

The yield on 10-year government bonds spiked by 200 basis points after 9/12 – an unprecedented spike.

Debt-service costs for government have already increased by over R15 billion over the next two years.

Net loan debt is projected by Treasury to be R2,2 trillion in 2017/18 fiscal year – 22% higher than 2015/16 – and budgeted to increase to R2,4 trillion in 2018/19, an increase of 32% since 2015/16.

In 2012/13, net loan debt of government was R1,2 trillion so in six years Treasury projects a doubling of debt to R2,4 trillion.

However, Treasury project nominal GDP to be only 55% higher by 2018/19 at R5,2 trillion compared with R3,3 trillion in 2012/13. This GDP projection was on rather more optimistic assumptions and Treasury is likely to ink a realistic update.

Unsurprisingly, debt to GDP is on a continuously rising trend and heading toward 50% by 2018/19, close to double the figure when the current President assumed office.

Debt servicing is projected at R162 billion in 2016/17 and R179 billion in 2018/19. This means interest payments by 2018/19 will be R50 billion extra or 39% higher than the R129 billion in 2015/16 and R78 billion more than the actual interest bill of R101 billion in 2013/14.

Interest will be over 11% of total government spending, up from 7% a few years ago, so more than one rand in nine goes to service debt.

In a scenario of a 200 basis point increase becoming a fixture rather than a temporary spike, it would add R40 billion in service costs in 2016/17 or 3% of total expenditure. That is 24% of the health budget, 77% of the defence budget, 45% of the police budget and equal to 100% of the budget for law courts and prisons.

To put the additional R50 billion of interest over three years within context of the current Treasury scenario, it compares with the R29,4 billion set aside as transfers and subsidies for higher education institutions in 2016/17 – 2% of the total budget. The additional cost of servicing growing debt – which compounds – is enough to sharply reduce university tuition fees and invest more in varsity infrastructure.

Treasury recently said, “debt-service costs remain the fastest-growing spending category… and continues to crowd out resources for policy priorities.”

In fact, Treasury documentation over an extended period has been ominous with regards to the fiscal trajectory – even a politician with a rudimentary understanding of finances giving a cursory rejoinder to the words, figures and advice would have cause for alarm. Yet, escalating profligacy has occurred despite Treasury doing its level best to influence rational policymaking.

Treasury is a bulwark for what is proper and sensible. Whilst the Reserve Bank and the PIC could also be included in this safeguard camp, only the Treasury has a mandate to manage national government finances. If both the constitutional and legislative mandate is usurped there are dire repercussions for asset prices.

The overriding driver for bank share pricing remains bond yields. With the R186 back up to 9% from 8,45% on 19 August, this already has a depressive effect on share prices from a discount point of view.

When I value banks, I use various metrics but a cost of capital assumption is fundamental and it’ll vary depending on movement in government long bonds and if the beta needs to adjust.

Let’s assume that banks reflect overall market risk and thus a beta of 1,0 and that the equity risk premium is 5%.

For our starting point let’s apply a ten-year government bond yield of 8,45% - the level before the finance minister jitters of this past week.

We’ll further assume that bank’s grow earnings in line with nominal GDP over time, say 8%.

A 55 basis point increase in the ten-year government bond to 9%, which is what we have seen, reduces the present value of future earnings by 7,2% and thus the value of the share.

In an environment of positive sentiment, finance ministry clarity and doing all the right things to avoid a credit downgrade, then if the bond yield had to drop by 55 basis points rather than rise 55 basis points then all else equal the value rises by 8,2%. If this had to extend to a 110 basis point rise from the base case then the value rises by 17,6%.

However, if we have a repeat of Nenegate (let’s call it Pravingate) and we see yields spike by 200 basis points, which is what happened on Thursday, 10 December 2015, then the cost of capital soars and the present value of earnings falls by 22,5% from the base case. In an environment of contagion, the negative impact is likely to be greater than in a static modelling scenario.

Sensitivities table

We can’t project the future but we can look at what could be in varying scenarios. The state of government finances is poor and mismanagement rife in a number of areas. Treasury and the finance ministry require the technocratic latitude to bring about greater discipline, much improved governance, a reprioritisation of spending and curtailment of wanton cash drain. The alternative has painful implications for interest rates and the value of shares linked to interest rates.

Subscribe To Our Research Portal

Search all research

Let Us Help You, Help Yourself

From how-to’s to whos-whos you’ll find a bunch of interesting and helpful stuff in our collection of videos. Our knowledge base is jam packed with answers to all the questions you can think of.